|

|

Lion

lounging during the day

Photo by Bob Plunkett

|

Lions

are on the prowl.

By

day these kings and queens of the food chain are

snoozers lolling in the shade, but when night

falls in the hills that Afrikaners in South Africa

call the bush, the lions arise. These are huge

cats, ferocious carnivores with fangs the size

of fingers and as sharp as spikes, and at night

they're hungry - and searching for supper.

Through

the dark we suddenly find them, their golden coats

shining in the glare of a game tracker's spotlight.

The lions surround our open-top Land Rover in

a hunting party of six gaunt females of various

ages plus one adolescent male, his mane sprigged

in sporadic tuffs around a thick and muscular

neck. We're struck by the size and proximity of

the pride - they're as close as an arm's reach

from my wife Tanya and me as we huddle on exposed

seats in the wagon.

Did

I mention it's very dark?

When

the tracker's light moves away from each lion,

the predator disappears into the blackness, but

we know it's still close because of the sound

of a panting breath and the swooshy snap of tall

grass as enormous claw-packed paws plod through

the brush.

I'm

feeling like a feline hors d'oeuvre served up

on seats of the Rover, just waiting for plucking

by one of the powerful females. Yet our guide

and driver, a South African wildlife expert named

Duard Terreblanche, tells us not to worry about

lions leaping into the vehicle.

"They're

accustomed to seeing the wagons around them, so

they ignore us," Duard whispers. "Besides,

they're on the trail of a more interesting meal."

And

so they are. They're walking, silently but purposefully,

in a line through the bush with perhaps ten yards

separating each hunter.

"We

say they're on their way to McDonald's for supper,"

Duard says, explaining that the lions are probably

stalking the most common hoofed prey in this game

reserve, the Thompson's gazelle, a small but swift

and agile antelope. "You can even see McDonald's

arches in a black 'M' marking the rump of each

gazelle."

As

the lions proceed through the bush we follow in

the Rover, the tracker's light moving from one

cat to another although he's careful not to shine

the light into their eyes or point ahead of the

procession.

"The

light's allowed on the hunters, but we don't want

to give them the advantage by showing off the

prey," Duard tells us.

We

continue like this, a line of lions moving side

by side through the bush but trailed by a Land

Rover filled with spectators who have journeyed

half-way around the world to observe big cats

in the wild.

Then,

as quickly as a twig snaps from shrub, the lions

sprint into the dark.

|

Pride

of Lions Surrounding Their Prey

Photo by Bob Plunkett |

Deep

and throaty snarls are heard plus a high-pitched

yelp followed by a loud roar as fangs connect

with forgiving flesh of the antelope trapped by

a wave of pouncing lions. It's not a pretty scene,

and certainly not so to watch one animal die for

the nourishment of others, but it's electrifying

to witness this age-old drama played out by wildlife

in Africa, hunter connecting with the hunted in

the endless continuum of the food chain.

"What

do you want to see the most?" Tanya asks

me during our journey to South Africa and the

private game reserve at Ulusaba.

"I

hope to observe a kill," I tell her, explaining

that, despite being an impassioned proponent of

wildlife conservation, I understand that the struggle

between hunter and hunted and the rule of the

food chain is as much a part of natural order

of Africa as thunderstorms and brush fires. Also,

I want to see Africa's large cats - lions, leopards

and cheetahs, each unique in social behavior and

habits.

We

had already been on safari elsewhere in Africa.

We peered into the gaping mouth of a hippopotamus

on the Zambezi River of Zambia and observed herds

of elephant and giraffe, zebra and wildebeest,

on dusty plains in Zimbabwe.

Yet

we met few big cats on these treks.

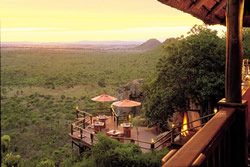

|

Ulusaba

at Sunset

Photo provided by Ulusaba |

One

place that specializes in close encounters with

Africa's wild cats is Ulusaba, a luxurious lodge

and game park owned by Britain's Sir Richard Branson,

the founder of Virgin Airlines.

Ulusaba

amounts to an elegant spa and retreat occupying

high ground in the midst of the Sabi Sand Game

Reserve. Sabi Sand abuts vast Kruger National

Park, which extends for two hundred miles or more

along South Africa's eastern border with Mozambique.

The area boasts the world's greatest concentration

of wild species and it teams with Africa's Big

Five game animals - lion, leopard, cheetah, rhinoceros

and the cape buffalo.

Tanya

and I spent four nights at Ulusaba and discovered

an uncommon safari resort in the wilderness that

caters to adventurous travelers wanting to get

extremely close to African wildlife.

Now

this isn't camping in the bush in the manner of

Hemmingway or Jungle Jim - tents pitched around

a fire pit and lions at bay just beyond the light

of the fire. Rather, accommodations at Ulusaba

more closely resemble a five-star hotel, only

it's located within Africa's largest preserve

of wild animals.

Facilities

consist of two different fortified encampments

- Rock Lodge and Safari Lodge - each a cluster

of thatched-roof bungalows surrounding a spacious

lodge house and gourmet restaurant with adjoining

swimming pool and sun decks. Each compound has

a well-stocked kitchen staffed by chefs trained

in fine cuisine as well as indigenous African

fare. Also, even in such a remote outpost there

are telephone and internet connections, a fitness

center rigged with top-notch equipment, plus the

Aroma Boma Spa, even a tennis court and nearby

private landing strip hacked from dense brush.

|

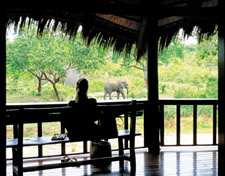

Elephant

sighting duriing a morning safari.

Photo provided by Ulusaba |

Daily

routines at Ulusaba revolve around the wildlife,

with early morning and late afternoon forays in

convertible Land Rovers to view the game. Between

these sunup and sundown safaris there's leisure

time for brunch and lounging by the swimming pool

or working out at the gym followed by an indulging

massage at the spa.

After

the evening safari, each lodge hosts a sumptuous

candlelight supper involving multiple courses

and perhaps a taste of wild game such as kudu

or impala.

During

daylight safaris we encounter an ark's assortment

of game - giraffes with their long necks stretching

into thorny acacia trees to munch on tender leaves,

elephants bathing playfully at a water hole as

hippos eye them with only twitching ears and nostrils

evident above the water line, herds of menacing

horns on cape buffalo lurking in shadows of the

bush, or lions, napping in a meadow.

Over

several days we track a lanky female cheetah and

three youngsters as these endangered creatures,

swiftest runners in the animal kingdom, hunt for

impala. One morning, mother parks the kids in

a field, then out-sprints the antelope and holds

its neck in her jaws until the young ones arrive

to render the coup de grace. And as cubs subsequently

feast on the prey, mother cheetah, still panting

from her race, stands over her wards as sentry.

"Uh-oh,"

says Duard as his binoculars pick out the spots

of a leopard lurking in tall grass.

Mother

cheetah also sees the leopard and for ten tense

minutes the two big cats eye one another from

a distance as the cubs devour the little antelope.

We

wait for a confrontation between leopard and cheetah,

but it never comes. Instead, the leopard eventually

slinks off in the grass, with cubs still unaware

of the danger.

"That must be a female," Duard speculates,

"because a male leopard would come right

up and take the kill."

And

one reason the cheetah population continues to

shrink, he says, is because these are Africa's

only large cats that will not stand and defend

a kill.

|

Taking

a break from the evening safari.

Photo provided by Ulusaba |

At

sundown during our evening safaris the Land Rover

stops in a meadow as Duard and his tracker, a

Zulu tribesman who uses the Anglican name of Simon,

retrieve from the tail of the Rover a folding

table and picnic basket, then set out refreshments

- high tea of sorts in the bush at Ulusaba.

We

sip and munch while standing around the vehicle,

careful not to stray too far because we've seen

the kind of critters that dwell here.

But

on several afternoons, Duard and the tracker Simon,

each shouldering a powerful hunting rifle, escort

us on a hike into the bush where we physically

place ourselves at risk in the African food chain.

We walk for a mile or so, crossing river and meadow

and following game paths but stopping to observe

even the lowly dung beetle toiling to roll a tiny

ball of elephant dung. Elephants are Africa's

behemoth eating machines, according to Duard,

consuming up to a hundred pounds of fodder every

day but digesting less than half the foliage they

eat. Their droppings, still rich in nutrients,

fuel many other creatures.

Duard

points out the three-foot-long monitor lizard

camouflaged against brown bark of a tree. He picks

off a three-inch-long African chameleon flashing

vivid green skin against the green leaf of a tree,

spies a stately kudu and calf across a clearing

and finds in the sand the tell-tale tracks of

lions, each paw print wider than the span of my

hand.

Near

a water hole our guide discovers the scat from

resident hippos.

"They

venture out of the pools at night to forage, but

watch out because a hippo is the most dangerous

animal in Africa." If a person gets between

a hippo and the sanctuary of its water hole, he

says, the animal will charge, swinging that huge

head back and forth with mouth agape to expose

sharp tusks that can slice a person in half.

|

Game

viewing from the resort.

Photo provided by Ulusaba |

On

our last evening at Ulusaba, we're in the safari

wagon searching for rhinos.

Shy

and solitary in nature, the white rhinoceros is

elusive at Sabi Sand. We drive around for several

hours looking for these animals that seem as big

as box cars yet all we find are occasional tracks

on the trail plus their spore - lots of spore,

in fact, indicating a very large rhino.

We

return to camp without sighting the creature,

although if we catalog all face-to-face encounters

with the wild things of Ulusaba it amounts to

an incredible show. To prove it, we load the best

images from a digital camera into our laptop computer,

then get on the Internet from a bungalow at Safari

Camp and send home digital post cards.

"Greetings,"

we write, "from the lion's den."

Ulusaba

- safe haven among the wild things

by Tanya Plunkett, Travel

World Syndicate |

|

Ulusaba's

Rock Lodge

Photo by Bob Plunkett |

The

name Ulusaba means "place of little

fear" because the towering pinnacle

where Rock Lodge stands provided the perfect

lookout point for ancient Shangaan warriors

who once hunted here.

Nowadays

there's little for visitors to fear at Ulusaba,

despite the remote location in a wilderness

populated by the most ferocious animals

in Africa.

But

it didn't seem that way at first.

When

my husband Bob and I arrived at Ulusaba,

following several days on jets from the

United States plus a long ride from the

nearest airport, we spotted a two-track

trail leading out of camp and I asked our

guide, Duard Terreblanche, if that would

be a safe place to run for our daily exercise.

"You

can't run outside the camp," he told

us, "because the lions might get you."

I

thought he must be kidding, although later

I would discover just how many fierce animals

inhabit the seemingly tranquil forests surrounding

Ulusaba's camps.

Duard

suggested we use the gym instead. It's at

Rock Lodge on the granite peak called a

koppie. The highest bungalow, reached by

many steps up a suspended catwalk, houses

Ulusaba's fitness center. We find Cybex

weight-lifting machines, StairMaster steppers

and deluxe treadmills, the type of equipment

stocked by the best gyms in the United States.

So our runs at Ulusaba take place on the

treadmills, which face a floor-to-ceiling

window overlooking a water hole in the forest.

During my first steps on the treads, I watch

as three elephants wade into the pool.

|

Safari

Lodge's Rope Bridge

Photo by Bob Plunkett |

While

Rock Lodge stands atop the koppie, Safari

Lodge is half a mile away built on piers

over banks of the Mabrak River which, except

during the rainy season, resembles a dry

river of rocks. Swinging rope bridges across

the river connect several isolated bungalows

to the main compound. Each camp has an electrified

fence around the perimeter, with boardwalks

and sidewalks linking bungalows to the main

lodge and dining room.

Quarters

at the camps are constructed from stone

and native hardwoods, then decorated in

distinctive colors of a specific African

tribe. A four-poster bed in the wood-floored

room is draped in diaphanous white mosquito

netting, while the spacious bathroom contains

a cave-like shower with cascading waterfall

plus a zebra-striped tub strategically set

near a picture window so you can watch a

parade of game even while soaking.

In

the evening an armed sentry awaits to escort

you to a dinner by candlelight. Still, monkeys

come into the camp through the towering

fig trees and one night a leopard lurked

in granite crevices above Rock Lodge. And

those lions are always out there - we hear

them during the night from our bed, along

with the sing-song bray of the hyena and

honking snorts from hippos.

In

the midst of this menagerie, though, we

find chefs capable of turning out menus

worthy of Michelin's favored stars. A request

for low-fat fare brings the head chef to

our quarters for consultations, and the

meals that follow are creative in selections

and brilliant in execution - including African

stock like the yam and exotic-for-the-bush

spiny lobster.

One

dinner under the stars on decks at Safari

Lodge is interrupted by passing visitors

- a pride of lions meandering across the

river. We watch them from the deck as the

cats fade into the night, then return to

the table with goose bumps tingling.

The

tab for safari at a private game reserve

like Ulusaba may seem steep - about $1,000

in U.S. dollars per night for a couple sharing

quarters. But that fee covers a lot. Included

in the day rate are luxurious accommodations

in a romantic room with en suite bath and

sun deck, the two-per-day game drives with

a ranger and tracker plus optional hikes

on foot into the bush, access to the swimming

pool and fitness center and tennis courts,

all meals and all beverages from a well-stocked

bar including fine wines, even same-day

laundry service with your safari suits starched

and pressed and returned to your quarters

each evening.

|

Resort

Room

Photo provided by Ulusaba |

Ulusaba,

the private game reserve of Sir Richard

Branson, is situated in the western section

of the Sabi Sand Game Reserve abutting Kruger

National Park in Mpumalanga province of

South Africa. Operating year-round, the

resort consists of two separate camps -

Rock Lodge and Safari Lodge. Accommodations

include all food and beverages, twice daily

game viewing drives, optional walking safaris,

access to lounges, swimming pool, fitness

center and tennis court, plus daily laundry

service.

Per

day rates for two people sharing quarters

begin at 7,000 South African Rand (current

conversion rate of $1,040 in U.S. dollars).

Access

is by charter single-engine aircraft landing

at Ulusaba's private air strip or commercial

air service via South African Airways from

Johannesburg to Kruger Mpumalanga International

Airport, coupled with a car transfer by

road. Johannesburg has daily international

flights from Atlanta, New York, Sao Paulo,

London, Amsterdam, Paris, Frankfurt, Hong

Kong, Singapore and Sidney on such carriers

as South African Airways, Varig, British

Airways, Virgin, KLM, Air France, Lufthansa,

Cathay Pacific, Singapore Airlines and Qantas.

Contact

Ulusaba at the United States office, (800)

557-4255 or (203) 602-0300, or by email

at sanctuare@sanctuare.com. Or visit Ulusaba's

website at www.ulusaba.com |